Nazi Town, USA

Season 36 Episode 1 | 52m 32sVideo has Audio Description, Closed Captions

The story of the German American Bund, a pro-Nazi group active across the US in the 1930s.

Nazi Town, USA tells the story of the German American Bund, a pro-Nazi group which in the 1930s had scores of chapters across the country, representing what many believe was a real threat of fascist subversion in the United States. They held joint rallies with the KKK and ran summer camps for children centered around Nazi ideology and imagery, melding patriotic values with virulent anti-Semitism.

See all videos with Audio DescriptionADCorporate sponsorship for American Experience is provided by Liberty Mutual Insurance and Carlisle Companies. Major funding by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation.

Nazi Town, USA

Season 36 Episode 1 | 52m 32sVideo has Audio Description, Closed Captions

Nazi Town, USA tells the story of the German American Bund, a pro-Nazi group which in the 1930s had scores of chapters across the country, representing what many believe was a real threat of fascist subversion in the United States. They held joint rallies with the KKK and ran summer camps for children centered around Nazi ideology and imagery, melding patriotic values with virulent anti-Semitism.

See all videos with Audio DescriptionADHow to Watch American Experience

American Experience is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Buy Now

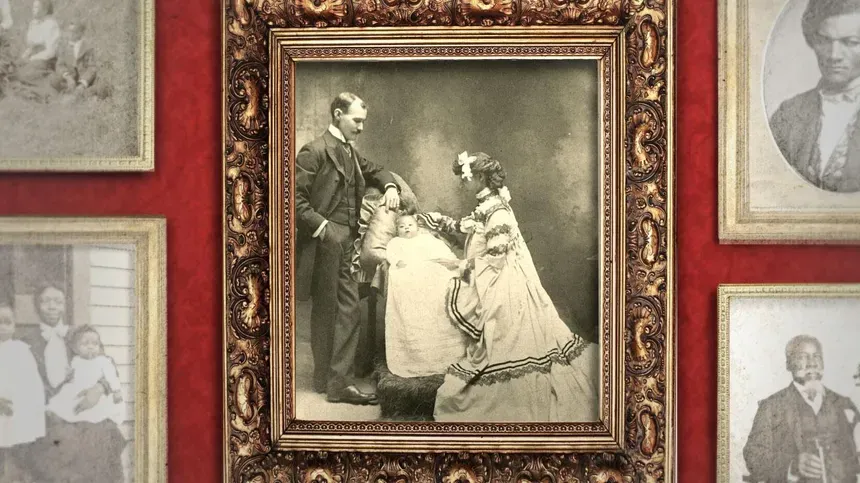

When is a photo an act of resistance?

For families that just decades earlier were torn apart by chattel slavery, being photographed together was proof of their resilience.Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipANNOUNCER: The following program includes derogatory images and language in historical context for educational purposes.

Viewer discretion is advised.

♪ ♪ NEWSREEL NARRATOR: In ever-increasing numbers, the nation's youth has been going away to camp.

This year has seen more boys and girls at camp than ever before.

All of them have enjoyed common experiences, common adventures.

♪ ♪ Building muscle, learning fellowship, acquiring camp spirit.

♪ ♪ (rifle shot) ARNIE BERNSTEIN: It looked like any summer camp in America.

It looked normal.

But it wasn't normal.

It was Nazi camp.

In the 1930s, there were these camps all across the country.

SARAH CHURCHWELL: They were indoctrinating centers.

That's what they were for.

As well as for protecting the purity and the health of your superior breed.

HART: The camps were the creation of something called the German American Bund.

The Bund's vision was an America ruled by white Christians, and they thought that Nazism was entirely consistent with American ideals.

RALLY LEADER: My fellow Americans, what would George Washington think and do were he alive today?

Would he not plead with the thinking, the loyal and law-abiding people, the true Christian Americans?

LEAH WRIGHT RIGUEUR: The German American Bund is after power, they're after influence, within the very fabric of the United States.

They want their ideas to become mainstream, and they want people to embrace those ideas.

WILLIAM HITCHCOCK: They were against democracy.

And thought that America would be a kind of star in a constellation of pro-Nazi governments around the world.

♪ ♪ RIGUEUR: We assume that democracy is something that all Americans embrace.

But in the 1930s, there were people in the United States who were ready to try something different.

(crowd chanting) BEVERLY GAGE: In the 1930s, lots of Americans thought the whole social order was about to collapse.

Capitalism, democracy, they were done for, and something else was going to have to come along to take its place.

And a lot of people thought that was going to be fascism.

SINGERS (on radio): ♪ Gave proof through the night that our flag ♪ ♪ Was still there ♪ ♪ O say does that ♪ ♪ Star-spangled banner yet wave?

♪ ♪ O'er the land ♪ ♪ Of the free... ♪ HITCHCOCK: In the 1930s, the largest fascist group in the United States was the German American Bund.

"Bund" simply means organization.

But, fundamentally, this is an American organization.

They believe in a pure nation.

They believe in a strong nation.

They believe that government is best when it is organized in a hierarchical way with a powerful dictator at the top, and that this would improve America.

We have no time, nor excuse, to be idle, so march along with the Bund!

GAGE: The popularity of the Bund showed that there were certain elements of the fascist vision that had real appeal in the United States.

BUND SPEAKER: We have to fight for our rights!

CHURCHWELL: When you look at American fascism in the 1920s and '30s, the outcome of German fascism had not yet happened and was not known.

We have the benefit of hindsight, but Americans at the time didn't know where it was going to go.

(crowd singing) HART: As foreign as this might seem, fascist ideology tapped into some deep historical realities, dark realities, in America.

So the United States was fertile ground for groups like the German American Bund to emerge.

GAGE: The United States in the 1920s is a place of powerful divisions.

It is a place of deep antisemitism and it is a place that has very formal racial segregation.

HITCHCOCK: The separation of races was something that Americans have been doing for centuries, but they've been doing it legally since the end of the Civil War through Jim Crow, the body of laws, as well as habits and customs, that kept white and Black people apart in public spaces.

In fact, the whole structure of racism in America had broad popular support.

GAGE: In the 1920s, one of the biggest organizations in the United States was the Ku Klux Klan, which was not only anti-Black, it was anti-Jew, it was anti-immigrant, and those weren't marginal ideas.

HITCHCOCK: In 1924, five million people were in the Ku Klux Klan, including a couple of dozen senators and congressmen.

The Klan's basic message was a combination of white Christian nationalism combined with family values, which was a message that was appealing to millions of people.

STEVEN ROSS: Father Coughlin, Charles Coughlin, known as the radio priest, every week went on the air to 14 million listeners, basically warning the country that Jews were destroying it.

COUGHLIN (over radio): We are Christian in so far as we believe in Christ's principle of love your neighbor as yourself.

And with that principle, I challenge every Jew in this nation to tell me that he does not believe in it.

(cheers and applause) ROSS: Antisemitism is rife in the United States, and at this point, it's out in the open.

The most famous antisemite in America was probably Henry Ford.

HITCHCOCK: Henry Ford was an inventor, an extraordinary capitalist, but he used his wealth to promote some of the most virulent antisemitic conspiracy theories.

He published a notorious book called "The International Jew," and had it distributed widely around the country.

Millions of people might have heard of this book, but never actually seen it.

Well, Ford took care of that.

CHURCHWELL: At that time, antisemitic and white supremacist ideas were supported by a pseudo-scientific movement that was wildly popular in Europe and in the United States called eugenics.

What is the bearing of the laws of heredity upon human affairs?

Eugenics provides the answer so far as this is known.

Eugenics seeks to apply the known laws of heredity so as to prevent the degeneration of the race and improve its inborn qualities.

CHURCHWELL: Eugenics said that white supremacy was biologically determined and could be proven.

As could the identities of the inferior, you know, so-called inferior races.

It rationalized white supremacism by apparently giving it a scientific basis.

Laws were based on these ideas.

RIGUEUR: In 1924, the United States passes the Johnson-Reed Act, which puts a quota system on people immigrating into the United States from Europe.

Under this new law, roughly 90% of them are going to come from northern European countries; a.k.a., white.

(man shouting commands) ROSS: All this led right wing groups like the German American Bund to believe that they would actually have a receptive audience in America.

Because, look, Americans had cast themselves as a white nation.

(cheers and applause) RALLY LEADER: We are decidedly not preaching un-Americanism or anything basically new.

We have an Asiatic exclusion act, Jim Crow laws, and a complicated system of immigration quotas differentiating even between the various white peoples.

It has then always been very much American.

(cheers and applause) HART: The leader of the Bund was a naturalized American citizen named Fritz Julius Kuhn.

Kuhn had some bold ambitions.

He presented himself as an American führer, and his vision was to become the absolute leader, the absolute dictator, of this organization he claims is going to take control of the United States.

Let me welcome you, in the name of our local unit of the German American Bund of Brooklyn.

And I'd like to tell you a few words about our purpose and aims.

HITCHCOCK: He imagined that he was going to build a distinctively American version of Nazism.

Because America's problem is that it has too many differences, it has too many races all mingled together, too many languages.

This country can't possibly survive for a long time in such a crazy state.

It should be organized, it should be disciplined, and it should be unified by one charismatic leader.

HART: Kuhn's path to the United States was somewhat typical for men of his generation who had lived through World War I... (explosion) ...only to experience the economic ruin that Germany went through in the early 1920s.

European society was devastated after World War I, and Germans, as the losing side of the war, were especially affected.

You had hyperinflation.

You had unemployed soldiers, unemployed workers, all desperate.

Everyone was looking for a solution.

(newsreel music playing) NEWSREEL NARRATOR (in Russian): ♪ ♪ CHURCHWELL: A lot of people thought that communism was the answer.

But others were very, very worried that revolutionaries were coming.

That property would be abolished and this infection would spread.

In Europe, one main ideological counter to communism was fascism.

GAGE: Our association of fascism with the Second World War, and particularly with the Holocaust, isn't a set of associations that anyone had in the 1920s.

HITCHCOCK: People looked at the fascist Italian dictator Mussolini and said, Mussolini has solved Italy's economic crisis by suppressing the communists, by getting rid of parliament, getting rid of divisive political parties.

And he's basically asked Italians to trust him and his vision of a united country.

CHURCHWELL: Fascism was a word that was coined by Mussolini to identify his political movement.

It says that in order to reclaim the strength and the purity and the nobility of your country, you need to purify your nation of "the wrong people" to get back to what the nation is supposed to be.

It's essentially a white nationalist movement, so a lot of Americans were intrigued by fascism, at least in its Italian form.

I am very glad to be able to express my friendly feelings towards the American nation.

My fellow citizens, who are working to make America great.

ROSS: In Germany, Adolf Hitler's Nazi party is first seen as a very marginal group of thugs.

Hitler rises to power on one promise: to save Germany.

And to save Germany, he's going to get rid of the communists and the Jews.

CHURCHWELL: Fritz Kuhn was involved in the early days of the Nazi party.

He claimed that he had been part of Hitler's failed coup attempt in 1923.

HITCHCOCK: Kuhn is emblematic of this generation of young German men who feel that they are the victims of the outcome of the First World War.

They want unity, they want comradeship, but most of all, they want employment.

ROSS: So in 1924, he decides to do what many other Germans do: leave the country and come to America.

HART: German Americans and their descendants had been in the United States for a long period of time at this point.

There were actually multiple waves of German immigration to the U.S. BERNSTEIN: So Kuhn went to Detroit and got a job at the Henry Ford Hospital as an X-ray technician.

It was a hospital that had a policy of no Jewish doctors.

CHURCHWELL: It's an era of deep antisemitism, of legalized racism, of growing inequality across the United States.

And then the Great Depression begins.

♪ ♪ RIGUEUR: In October 1929, the stock market crashed with the subsequent onset of a massive depression.

GAGE: The stock market lost about 90% of its value.

In places where you had a largely foreign-born, industrial, working-class population, as many as 80% of those workers were out of work.

CHURCHWELL: In the depths of the Depression, a great many Americans started to ask themselves whether the American experiment was failing.

ROSS: In one poll of conservative professionals, something like a third of them said it was time for a revolution; some kind of change.

Whether it was going to be democracy, whether it was going to be communism, whether it was going to be fascism, all these ideas were finding supporters.

(cheers and applause) (crowd clamoring) (whistle blowing) RIGUEUR: The 1930s is a period that can be characterized by fear.

Fear of the other.

Fear of want.

Fear of losing everything.

ROOSEVELT: The only thing we have to fear is fear itself!

HITCHCOCK: Franklin Roosevelt comes into the White House in March of 1933 in the midst of the biggest economic and social crisis since the Civil War.

My most immediate concern is in carrying out the purposes of the great work program just enacted by the Congress.

RIGUEUR: His solution is to introduce a series of programs that come to be known as the New Deal.

There has not been another president that has introduced more legislation than Roosevelt did in his first 100 days.

♪ ♪ CHURCHWELL: American right-wing groups were rabidly opposed to Roosevelt's New Deal, which they saw as a communist plot, as a redistribution of property, and began calling it "the Jew Deal" because they said that Roosevelt was being manipulated by Jewish financiers who were pulling the strings.

GAGE: 1933 was also the year that Adolf Hitler came to power in Germany.

So there was a sense not only that there was a crisis at home, but that fascism was really beginning to take root around the world.

HART: Hitler puts Germany on what appears to be a very successful course.

Inflation is under control, and according to the Nazis' official figures, unemployment has all but disappeared.

Americans who see their own system in crisis are looking at fascism and Nazism as perhaps models that could be emulated in the United States.

So extremist groups pop up all over the country inspired by what's going on in Europe.

There was the Order of '76, there was the Black Legion, there was the Liberty League.

There were the White Shirts, the Black Shirts, and Brown Shirts.

There were the Silver Shirts.

PAPERMAN: Free speech stopped by Jew riot!

CHURCHWELL: They just proliferated.

♪ ♪ HITCHCOCK: In its earliest expressions, fascism was thought by many Americans to be a suitable answer to America's problems.

But there were others who opposed fascism from the beginning.

CHURCHWELL: Dorothy Thompson was one of the first female foreign correspondents for American newspapers and was working in Europe during the rise of fascism.

She could see the danger that it posed and she was very outspoken about it from very early on.

She had the honor, I think, of being the first American foreign correspondent to be ejected from Germany after Hitler came to power.

There seems to me to be a certain misunderstanding about, about the antisemitic end of the Hitler movement.

A great many people didn't believe that if they came to power they would carry this, carry this program out, but as a matter of fact they are doing what they have said for 13 years that they would do if they came to power.

HITCHCOCK: Another one of the great public figures of that era, Rabbi Stephen Wise, steps forward and says we are going to act.

We're going to mobilize against Nazism.

ROSS: Wise called for a boycott of all German products until Hitler stopped persecuting all minorities; not just Jews, but all minorities.

It led to a big decline in German imports.

This presents a challenge to Berlin, which is "How do we improve our reputation in the United States "while also pursuing our policies against the Jews here in Germany?"

ROSS: Rudolf Hess, the number two Nazi leader, was looking at the American situation and saying, "How are we going to offset this?"

And so he helped create the Friends of New Germany.

NEWSREEL NARRATOR: The membership card in the Friends of the New Germany.

Note the American emblem, and over it the Nazi swastika.

ROSS: People join the Friends of New Germany in the same way you would join the Masons, or the Odd Fellows, or the Elks.

HITCHCOCK: So Kuhn joins the Friends of New Germany and becomes the head of the Midwest district.

ROSS: It was one thing for Americans to say, well, Hitler's doing great things for Germany, um, from a distance.

But Americans didn't actually like seeing swastikas in their neighborhoods.

This began to turn American public opinion against the Friends of New Germany and against the Nazis.

BERNSTEIN: In the 1930s, there was a very strong Jewish presence in the mafia, and they had an army of Jewish prizefighters, guys who knew how to work their fists.

ROSS: At the time, about a third of professional boxers were Jewish.

And many of those Jewish boxers were very proud of their heritage and they had Stars of David on their trunks.

BERNSTEIN: They saw it as their duty to take on the Friends of New Germany.

In New Jersey, this army of boxers was called the Minutemen-- because they could be there in a minute.

ROSS: They would burst into open meetings of the Friends of New Germany and they would beat the stuffing out of them.

In Newark, New Jersey, they were so angry there was a massive brawl that lasted for hours until the police were able to get it under control.

The government in Berlin starts to feel that it's more of a problem than it is an asset, and in late 1935 they disband the organization.

The Friends of New Germany was no more, and Fritz Kuhn saw his opportunity, and seized it.

He said, you know, we have to re-form this group.

We have an infrastructure already in place with chapters all over the country.

HITCHCOCK: So in early 1936, Fritz Kuhn founds the German American Bund.

And Kuhn was trying to sell it as an American organization.

ROSS: What you begin to see in 1936 with the creation of the Bund is what I would call the beginning of star-spangled fascism.

The German American Bund is a patriotic, law-abiding and honor-bound fighting organization of loyal Americans of German extraction, fighting to exterminate Jewish, international, atheistic Bolshevism.

RIGUEUR: The German American Bund starts very deliberately cloaking itself in the explicit symbols of Americanness-- George Washington, the American flag.

HART: You have these bizarre mixtures of American symbols with the symbols of Nazism.

People dressed as Minutemen from the American Revolution standing on stage next to these Bund members in their own uniforms, or a man dressed as a Native American chief.

HITCHCOCK: Kuhn is trying to change the conversation a little bit by saying, "You can be a patriotic American and you can be proud of the Nazi government as well."

So he is going to try to square the circle, which is to make Americans and American citizens a part of an organization that is basically designed to propagate Nazism.

(people chattering) ROSS: The National Bund establishes its headquarters on the Upper East Side of Manhattan in the Yorkville neighborhood.

German was spoken in the streets.

The shops had signs in German.

If you walked through Yorkville in 1936, you could think you were in a German city.

The Bund also had a fairly extensive business arm.

New York City had beer halls where its members would gather, and these were often owned and operated by the Bund.

(singing in German) (singing continues) CHURCHWELL: Nationally, most German Americans were not supporters of the Bund, but the German American Bund had a great presence in New York, so it was deliberately provocative for the Jewish community because they were literally holding parades in front of Jewish people's homes.

We are American citizens and we demand our rights to be American citizens!

ROSS: Like Hitler, Kuhn wanted to establish a Reich that would last for a thousand years.

So he gets to work expanding the group.

HITCHCOCK: In 1936 and '37, the Bund has a period of real growth.

There were three big districts of the Bund in America, but there were 45 regional districts and then 80 smaller little branches.

They're all over the place in the West Coast, Midwest, and East.

HART: At its peak, the Bund attracts as many as 100,000 members.

And there were thousands of people who were also sympathetic to the Bund who were attending its events.

RIGUEUR: One of the best ways to get people on board is to target their children.

People can say, "Well, this is a good organization.

"It teaches them about the beauty of nature.

"It teaches them vital skills in life.

"And it's family friendly and family oriented.

"By the way, we hate Jews, we hate Blacks, we hate Catholics."

(singing in German) (singing in German continues) (song ends) CHURCHWELL: You get kids out of unhealthy city environments and put them into these summer camps.

It's all about making sure that your superior breed is kept separate from pollutants-- people of inferior races and ethnicities.

HART: Children are essential to the future of the movement.

They have to be physically primed to become the leaders of this Nazi Reich.

So there was a camp in upstate New York, Milwaukee, Chicago, Los Angeles, San Francisco, the Pacific Northwest.

There were camps located all over the country.

♪ ♪ BERNSTEIN: The grand opening for Camp Norland was July 18, 1937, and it was an event to be seen.

♪ ♪ There were more than 10,000 people there.

And this was in New Jersey, 60 miles outside of Manhattan.

♪ ♪ MAN (over speaker): I call upon all of you to join us in the battle for a socially just, financially independent, and Jew-free America.

HITCHCOCK: The biggest camp that the Bund built was Camp Siegfried, in Yaphank, Long Island.

It was a destination for lots of people from the New York area, not just during summer camp, but for rallies and picnics and gatherings throughout the year.

BERNSTEIN: There was a train every Friday direct from Penn Station to Long Island called "The Siegfried Special," and it would be packed with people getting away for the weekend.

♪ ♪ HITCHCOCK: Camp Siegfried was so popular, the Bund created a front organization called the German American Settlement League, which bought property so that they could establish, not only camps, but actual planned communities.

And at Yaphank, they did build a German-American settlement called German Gardens.

CHURCHWELL: The town that they set up named streets on Long Island after prominent Nazis.

So there was Adolf Hitler Street and there was Goering Street.

They had laws on the books restricting ownership.

So, unsurprisingly, this community was not willing to admit Jewish homeowners.

♪ ♪ HART: It was designed around the idea of creating an idealized sort of Nazi town.

♪ ♪ In the late summer of 1936, President Roosevelt calls J. Edgar Hoover, who's the head of the FBI, asking him to look into the activities of Nazis in the United States.

One of the first things that the FBI sets out to investigate is the German American Bund.

Sieg...

CROWD: Heil!

Sieg...

CROWD: Heil!

Sieg...

CROWD: Heil!

GAGE: Ultimately, the FBI produces a thousand-page report which really lays out some of the more outrageous aspects of this organization.

The pro-Nazi imagery, the pro-Hitler sentiments, the antisemitism-- all of it's there, but Hoover was not terribly interested in taking this on.

Why is Hoover sitting on his hands doing nothing with the Nazi fascist threat?

The answer is actually pretty simple.

It's because he was a rabid anti-communist.

HOOVER: The Communist Party of the United States is not a political party.

It is a way of life, an evil and malignant way of life.

HITCHCOCK: Like many Americans, Hoover thought "Well, I don't really like fascism, but I do like its anti-communist credentials."

So, people tolerated organizations like the German American Bund that were explicitly anti-communist.

RALLY LEADER: We stand beside you as Christian soldiers in your valiant fight against Jewish communism.

(applause) There is a movement to stop hate speech.

And, in fact, the New Jersey legislature passes the race libel law.

You can't libel somebody because of their race, their religion, their color.

HART: This is, in some ways, a novel concept in law.

The problem with this is that groups like the ACLU immediately become involved and raise the obvious constitutional objection of how can you possibly outlaw speech that is offensive to a particular group.

For all of the kind of horror of the idea of pro-Nazi forces acting in the United States, it's really not clear that they were breaking any particular federal law that existed at that point by engaging in the activities they were engaged in.

HART: Ultimately, the big test for the race libel law comes because of Camp Nordland, the German American Bund camp in the state of New Jersey, because of speeches that were defamatory towards the Jewish community.

RALLY LEADER: We know that the Jew is most concerned with maintaining his stranglehold on the financial systems of the world.

(crowd cheering) HART: Ultimately, there is a conviction of nine Bund members for violating the race libel law, but that's struck down by the New Jersey State Supreme Court.

In the end, the ACLU publishes a pamphlet defending their decision to defend the free speech of Nazis.

RIGUEUR: This is the double-edged sword of the First Amendment.

It is a fundamental American right to be allowed to say horrible things, but the protection of the right to be hateful is what allows these ideas to proliferate.

♪ ♪ (car horns honking) HITCHCOCK: In early 1937, a Chicago newspaper, the "Chicago Daily Times," decides it's going to send reporters incognito into the world of the German American Bund.

♪ ♪ BERNSTEIN: John and James Metcalfe were brothers, born in Germany, were both reporters for the "Chicago Daily Times."

They were assigned to go undercover and infiltrate the Bund.

They had German birth certificates and they could speak German.

So they had the perfect credentials.

HITCHCOCK: John had a little toothbrush mustache, if that might be a little familiar, and looked the part.

He approaches the Bund headquarters in New York and works his way into the organization.

Metcalfe goes by an alias, Helmut Oberwinder, and very quickly ingratiates himself with Fritz Kuhn.

♪ ♪ HART: Because he's willing to dedicate himself to the cause, within just a few months, John Metcalfe becomes Kuhn's right-hand man.

And Kuhn dispatches Metcalfe as a personal emissary to local and regional Bund chapters.

So Metcalfe travels all over the country, visiting with various Bund leaders.

And, all along the way, he's filing reports back to his paper.

Everything from how a local Bund chapter might be completely inept-- they were more interested in having drinking parties than politics-- to Bund leaders scoffing at Kuhn's authority, all the way to individual rank and file members talking about their ambitions to actually overthrow the U.S. government and establish a Nazi dictatorship.

♪ ♪ HITCHCOCK: In September of 1937, the "Chicago Daily Times" drops the bomb.

They publish a series of articles on the German American Bund and they don't hold back.

♪ ♪ ROSS: These stories came out one after the other.

These exposés of how the Nazis in America are trying to undermine the American people, the American government, and the American way of life.

HART: The Metcalfes heard whispers inside the Bund's inner circle of something called Der Tag, which translates to "the day."

The day when the Bund believes there will be a fascist revolution in the United States.

BERNSTEIN: This would be the day that there would be an insurrection.

They would take over the United States government, and the swastika would fly above the Capitol.

The Metcalfe scoop really galvanizes public opinion against the Bund, and Congress begins to enter the discourse about what should be done about subversive groups in the United States.

Congressman Martin Dies, Jr. becomes the chairman of what will come to be called the House Un-American Activities Committee, or HUAC.

Tactics of communists, Nazis, and fascists are now endangering this country.

America must wake up to its danger.

HUAC PROSECUTOR: To whom were you sending these letters?

I sent that to a list of approximately 150 people.

GAGE: HUAC was very much in the mindset that there were an array of subversive organizations that needed to be investigated, and that a lot of them actually were on the right.

HART: John Metcalfe was the first witness called before the committee.

And there's incredible images of him giving Martin Dies and the committee the Nazi salute from the witness table, and then he showed them photos of how the Bund was preparing some sort of military coup.

ROSS: What were we going to be as a nation?

Because what the Bund wanted America to be was a nation that was proud of its white Aryan past.

But there were people who stood up for the right cause, who stood up for what we think of as American ideals.

CHURCHWELL: Dorothy Thompson had interviewed Hitler in 1931, and was very clear about the risks that he posed, and not just to Europe.

THOMPSON: The classical end of all pure democracy is the popular tyrant.

And incidentally, all successful tyrants throughout history have been popular idols.

CHURCHWELL: In 1938 alone, she gave more than 50 speeches about the importance of democracy and fighting fascism.

And her radio broadcasts reached more than five million people.

THOMPSON: The tyrant, said Machiavelli, must pose as the friend of the people, as their champion against the rich and aristocratic, as the incorporation of the people's will.

They must be made to feel that through him, in his person, they are actually ruling.

This was the formula of Caesar, and it's the formula of Stalin, Mussolini, and Hitler.

Her point was, "Never be complacent."

Her point was, "This can happen anywhere, and you have to be on your guard."

♪ ♪ ROSS: On November 9, 1938, in hundreds of cities across Germany, we have Kristallnacht-- "Night of the Broken Glass."

♪ ♪ (crowd clamoring) (glass shattering) For two nights, Jewish businesses are destroyed.

♪ ♪ Their homes ransacked.

♪ ♪ Synagogues are burned.

♪ ♪ 30,000 Jewish men are rounded up and sent to concentration camps.

HITCHCOCK: Americans now knew that Nazi Germany wasn't just a normal country with a fascist dictator.

It was a malevolent force.

HART: In the aftermath of Kristallnacht, the Bund's tactics are very provocative in the eyes of most Americans.

Hut!

HART: But rather than disappear from the public eye, the German American Bund decides on mass provocation.

HITCHCOCK: By the end of 1938, the Bund made it clear that what they wanted to do was to show "That we are popular, "that we are relevant, "that we're fulfilling our ambition "of making German Americans into "good Nazis and Americans at the same time.

How can we do that?

Let's have a rally."

♪ ♪ BERNSTEIN: People appealed to Mayor LaGuardia, and said, "How can you allow this to happen?"

LaGuardia said they have every right to do it, and he wasn't going to stand in the way.

It was the First Amendment.

ROSS: In those days, just like today, New York City had the largest Jewish population in America.

Of course there had been fascist demonstrations before all around the country, but the Bund was going to Madison Square Garden in the center of the Jewish-American world.

(indistinct chatter) BERNSTEIN: Over 20,000 Bundists were admitted inside the Garden that night.

Outside were tens of thousands of anti-Bundists wanting to get inside.

(indistinct shouting) (drum and bugle corps marching) (drumming continues) MAN: O.D.s.

Attention!

I pledge undivided allegiance to the flag of the United States of America and the Republic for which it stands, one nation, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all.

(applause) HART: Because of the visibility of this event, there had been a sort of general assumption that the Bund speakers would refrain from their most hateful speech, especially against Jews.

But that proves not to be the case.

GERHARD KUNZE: The Jew is a thousand times more dangerous to us than all the others by reason of his parasitic nature.

(cheers and applause) CHURCHWELL: Also present that night was the indomitable Dorothy Thompson, who was furious that this rally was taking place.

And amidst 22,000 fascists, she started shouting "Bunk!"

BERNSTEIN: Dorothy Thompson didn't hold anything back.

She went there to heckle.

She went there to cause a fuss.

(crowd shouting) CHURCHWELL: There is footage of Dorothy being hustled out.

Bodily thrown out of Madison Square Garden.

(car horns honking) ROSS: Inside the Garden, the final speaker is Fritz Kuhn himself.

KUNZE: We love him for the enemies he has made.

Ladies and gentlemen, Mr. Fritz Kuhn.

(cheers and applause) KUHN: Ladies and gentlemen, fellow Americans, American patriots.

If you ask what we're actively fighting for under our charter-- first, a socially just, white gentile-ruled United States.

Second... (applause) gentile-controlled labor union, free from Jewish Moscow-directed domination.

(applause) (rumbling, indistinct yelling) Wait, wait!

(men shouting) ROSS: A 26 year-old Jewish plumber named Isidor Greenbaum can't stand what he's hearing, and he runs onto the stage.

Stormtroopers grab him and are beating the hell out of him.

(crowd shouting) They could have killed him, except the police came in and stopped the fight.

(crowd clamoring) Be seated, please.

One fanatic don't make any difference, ladies and gentlemen.

(crowd shouting) (indistinct shouting, whistling) HART: So the rally really comes to this violent conclusion.

Outside, there's an almost riotous situation as protesters clash with the police and with Bund members.

(indistinct shouting, clamoring) BERNSTEIN: After the rally, New York Mayor LaGuardia was furious that this thing had happened in his city.

So he called his district attorney, Thomas Dewey, and said, "We can't get Fritz Kuhn for what he says.

But there's got to be another way to get him."

So his office started investigating.

♪ ♪ Thomas Dewey discovered that Kuhn had been using money from the Bund coffers to pay for his romances.

HART: Throughout his leadership of the Bund, Kuhn has maintained a network of mistresses across the country.

And he's used some of these funds to not only pay for his personal expenses, but also those of his lady friends.

NEWSREEL NARRATOR: The law books a would-be American führer on charges of grand larceny and forgery.

He's Fritz Kuhn, Bund leader and friend of Hitler.

But right now, his chief task is to explain about some $14,000 he's accused of stealing from his followers.

ROSS: Fritz Kuhn is found guilty of embezzlement and tax evasion, and he's sentenced to two-and-a-half to five years in prison.

HART: As Kuhn is sitting in Sing Sing Prison, he learns that Hitler has invaded Poland, and war has now broken out in Europe for the second time in a generation.

Debate is raging all over the country about whether the U.S. should even take sides in the war in Europe.

CHURCHWELL: There was a coalition of unlikely bedfellows of people who wanted to keep the United States out of the war for different reasons.

There were big business interests, there were pacifists, and then there were Nazi sympathizers.

So, all of these people formed this coalition called America First, and Charles Lindbergh became their spokesperson.

I have been forced to the conclusion that we cannot win this war for England, regardless of how much assistance we send.

(cheers and applause) That is why the America First Committee has been formed.

HART: Lindbergh had first come into prominence in 1927 when he was the first man to fly solo across the Atlantic.

He's a true national hero, and one of most famous men in the world in this period.

At its peak in mid-1941, America First has 800,000 members nationwide, dwarfing any other nonpartisan political organization of the era.

The imminent danger of war lies in the action taken by President Roosevelt and his supporters.

I appeal to all Americans, no matter what their viewpoint on the war may be, to unite behind the demand for a leadership in Washington that stands squarely upon American tradition.

(cheers and applause) GAGE: Lindbergh not only criticizes the Roosevelt administration, but also begins to really flirt, in pretty overt ways, with pro-Hitler sentiments, with antisemitism here at home, and becomes kind of the hero of the, to some degree, anti-war, and to some degree, pro-Hitler right.

HART: Another belief of the Bund was that after the fascist revolution, after "Der Tag," some leader will be swept into power on the Bund's political platform.

Now, who is this leader?

Fritz Kuhn might be one option, but the name that is whispered more commonly is Charles Lindbergh.

CHURCHWELL: There was talk of him running for president.

And, in fact, the America First Committee was organizing itself into a political party when Pearl Harbor happened, and everything, you know, unfurled differently.

(explosion booming) ♪ ♪ HART: Japan attacks Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, and the U.S. declares war against Japan.

A few days later, Hitler and Germany declare war on the United States.

(booming) GAGE: With the United States entering the war, you begin to get new laws that require non-citizens in the United States to register with the federal government.

March!

GAGE: You get laws like the Smith Act, which says that any group that advocates for the violent overthrow of the U.S. government can be subject to a whole host of criminal penalties.

ROSS: So after he's released from prison, Kuhn was then convicted a second time and given a second jail sentence for never having registered as a foreign agent of the German government.

And then, in 1945, he's stripped of his citizenship and sent back to Germany.

The Bund as an organization collapsed.

But, of course, the people who were in the Bund didn't then disappear.

The end of the Bund just meant that they blended back into American life.

♪ ♪ RIGUEUR: They go on to run businesses.

They go on to be doctors, and dentists, and police chiefs.

So when we say a group has disappeared, in a lot of ways that means nothing, because until the ideas are actually gone, it's still there.

It's the ideas that matter.

BERNSTEIN: Fritz Kuhn tapped into something that was, unfortunately, I wouldn't say just part of the American makeup, but part of human makeup.

The part that we don't like to look at.

HITCHCOCK: America triumphantly wins the Second World War, which justifies a sense of pride and recognition of sacrifices made by Americans to defeat Nazism.

But there's not so much a reckoning with the ideology that had motivated organizations like the Bund.

Those questions go unasked and unanswered after World War II.

There's this huge wish to simply forget about the fractious politics of the 1930s.

To think that groups like the Bund were all something that couldn't possibly present a serious threat to American democracy.

GAGE: It was unlikely that an avowedly pro-German organization was going to become the vehicle through which fascism came to America.

But it doesn't mean that that can't or won't happen.

♪ ♪ CHURCHWELL: The history of the German American Bund reminds us that fascism is ultra nationalist.

In other words, there's no such thing as foreign fascism.

Fascism is always homegrown.

♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪

Video has Closed Captions

The story of the German American Bund, a pro-Nazi group active across the US in the 1930s. (1m 26s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipCorporate sponsorship for American Experience is provided by Liberty Mutual Insurance and Carlisle Companies. Major funding by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation.