Beyond the Lens: What These Walls Won't Hold | Adamu Chan

Clip: Season 12 Episode 3 | 10m 26sVideo has Closed Captions

A conversation with WHAT THESE WALLS WON'T HOLD's Adamu Chan.

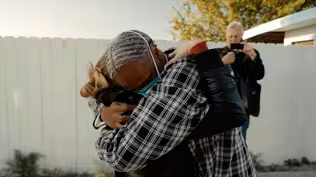

Director Adamu Chan and Natasha Del Toro, host of America ReFramed, talk about WHAT THESE WALLS WON'T HOLD and the story behind the documentary. Chan, who was incarcerated at San Quentin State Prison, shares why he chose to focus on the relationships between people inside the walls and the loved ones on the outside. The director also opens up about his own experience, impact, and filmmaking.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Funding for America ReFramed provided by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, Wyncote Foundation and Reva and David Logan Foundation.

Beyond the Lens: What These Walls Won't Hold | Adamu Chan

Clip: Season 12 Episode 3 | 10m 26sVideo has Closed Captions

Director Adamu Chan and Natasha Del Toro, host of America ReFramed, talk about WHAT THESE WALLS WON'T HOLD and the story behind the documentary. Chan, who was incarcerated at San Quentin State Prison, shares why he chose to focus on the relationships between people inside the walls and the loved ones on the outside. The director also opens up about his own experience, impact, and filmmaking.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch America ReFramed

America ReFramed is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipADAMU: We're all inside of this place trying to find our way out of here, but also trying to find a way to be together in spite of the separations that are inherent in the prison structure.

DANIELLE: This was 1993, the last day I was with them in the free world.

KRISTAL: The prisons are so far, I mean hours, away from Philly.

I started the van service to keep families connected.

CROWD: Welcome home, welcome home!

ADAMU: What feels important is how we are building community by using the power of telling our stories to change the system that incarcerated us.

(upbeat music) KRISTAL: If any of y'all have any loved ones that's incarcerated, I encourage y'all to go see them because they are coming home.

DANIELLE: I am home but I am not free.

I am not free because my sisters are not free.

Free her, free her, free her, free her, free her!

STEVIE: I feel a deep responsibility to make sure that this moment doesn't pass.

- You got you out- LONNIE: No, we got me out.

KRISTAL: I feel like a little girl, like, ah, my mom and my dad.

DANIELLE: I'm just trying to figure this whole freedom thing out, what's my purpose.

DEL TORO: This is our Liberated Lives Meet the Makers conversation.

uncovering the silent struggles and triumphs of those touched by incarceration while aiming to bridge the gaps of societal narratives with reconciliation, resilience and redemption.

Filmmaker Adamu Chan tells his story of incarceration through the lenses of dignity and determination, and how he found positivity in the most confined space.

Adamu, you tell your story in such a unique way and you're using poetry, music to capture the power of your voice.

Why did you decide to take this approach?

- I think originally I had thought about telling a more journalistic piece about the COVID outbreak that happened at San Quentin and the organizing that I was a part of and a lot of other folks were a part of.

But it seemed like a more personal approach had more power and more impact.

And also I wanted to bring my friends into this, into the fold and tell the stories of the people that I was closest to through letters and through the writing that we shared across walls and the communication that we shared across walls seemed like the best way to do that.

- This is a Valentine's Day card from you, very cute.

You always gave me Valentine's Day cards.

Your presence in my life makes me a better more whole person.

That's right, you see?

- Did you have a filmmaking background?

- I did not, I had the privilege of learning filmmaking inside of San Quentin's media center.

And at the time, I really understood that privilege that we were maybe the only incarcerated people anywhere in the world that were able to have video cameras.

And as a crew, as a group of filmmakers inside that really informed our purpose that we had this platform that no one else had and we had to speak to something greater than ourselves, than our own personal stories.

More than anything else, what feels important is how we are building community by using the power of telling our stories to change the system that incarcerated us.

I carried that with me when I came out too.

I wanted to tell a story that reached across walls.

This was a film that I wanted to prioritize folks who are currently incarcerated as a primary audience.

I wanted to do this for them so that they could watch it.

And one of my impact goals was to try to get a national broadcast because I know that people inside watch PBS.

I watched it, it was a big part of my growth as a filmmaker, my interests and my way of seeing the outside world and expanding my imagination and connecting with other people's stories.

- Have your fellow inmates, friends, have they gotten to see the film and what reaction have you gotten from them?

- Yeah, so one of the issues with being a formerly incarcerated filmmaker is that there are some biases that exist with the administration.

I'm not just a regular filmmaker and maybe some of the things that I have done, maybe the film itself feels subversive and I haven't been able to show the film inside.

So this would be the first time that folks inside would be able to watch.

And so I'm really excited about that.

You know, beyond that, when I was inside, we were producing a TV show that was going out to all 36 prisons in California, and I know the impact of that.

I still see the impact of that.

Like when I'm out on the streets and I see people who are formerly incarcerated and they came from other prisons, they'll tell me, they'll be like, "I saw you on TV and those stories reached me."

So I know that this will have impact.

And for my friends and loved ones that are still inside who see what we've been able to do with this film, it already has a impact on them.

It has broadened their horizons.

I'm just excited for what this will open up for other folks, not just as filmmakers but as creatives, as organizers, as people who are trying to dream bigger than their circumstances.

- What were some of the important things that you wanted the audience to know about your story?

- This is a story about relationships and it's a story about communities.

And the dominate narratives about resistance against the correction system are these stories about Attica and about George Jackson and these violent uprisings, but I feel like people are resisting every day.

And some of these other stories are about families on the outside who are every day doing the work and the mothers and loved ones who are such an important part of this resistance which is just relationships like the relationships that people have and the relationships that people maintain that actually keep people alive.

- Relationships are active resiliency and a pushback against the isolation.

Isolation is actually a root cause of crime.

Without feeling loved, it's hard to love.

If you don't care, you're a dangerous person.

- Sometimes I feel like the focus is on the political work, the advocacy.

Those things are really important but I don't wanna understate the importance of people's connections with their communities and their loved ones.

Isolation, violence, these things are not helping anyone's mental health and in many ways exacerbating it, making it much worse.

And then we expect people to come home and function when they've been traumatized more than they were originally and carry the shame and stigma of having a criminal record.

- How are you hoping that your film is received?

- I think back to when I was in solitary and when I got there I felt very alone.

And the person in the cell next to me reached out and asked me if I needed some food, asked me if I needed some cosmetics, if I needed a book to read.

And when the books came through the cell doors, I read Malcolm X and I read Audre Lorde and I read Assata and they were there with me.

And every day when it was mail call when I received a letter, my loved ones were there with me.

And so I think about this kind of black tradition of sharing our stories and how it bridges the gaps across the diaspora and how we build solidarity with each other through that, how we feel not so alone in the most isolated places.

For the first time in almost 12 years in prison, I feel connected to a purpose.

How we raise each other, raise our spirits together and I hope the film will play some small role in that, in bridging gaps and bridging the distances and getting people to believe in solidarity.

I think it's something that's transformed my life and I've seen it transform other people's lives and people are doing it every day.

And I just think that this is another way to exercise that muscle.

- How are you readjusting to life outside of prison?

- You know I've been privileged to be a part of a community of folks who come home and who have supported each other.

But it's difficult.

You go through different phases of processing what you've been through and coming to grips with it.

This is my fourth year of being home.

It's difficult.

The first year is you wake up every day and everything's beautiful and it's a blessing to be home.

And then as you move through it, things get more difficult.

Things begin to settle and you start coming to terms with what's happened to you and what's happened to the people around you.

I can't help but think of all those who are still behind the walls of San Quentin.

The psychological and emotional distance that cuts through the core of what feels like one of our most human needs, to be deeply connected to others.

I mean, I don't think the prison system works and these issues of safety that people have so much anxiety and fear about can be dealt with in different ways when we recognize everyone's humanity and the fact that everyone deserves love and care.

DEL TORO: Adamu Chan, thank you so much for spending time with us to talk about your film, What The Walls Wont Hold.

What These Walls Won't Hold | A Second Chance

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S12 Ep3 | 1m 9s | An incarcerated man sees a second chance on the outside for himself and his family. (1m 9s)

What These Walls Won't Hold | Best Friends

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S12 Ep3 | 2m 27s | Best friends Adamu and Isa share their hopes and dreams while Adamu is incarcerated at San Quentin. (2m 27s)

What These Walls Won't Hold | Healing Power of Filmmaking

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S12 Ep3 | 22s | Director Adamu Chan opens up about finding filmmaking inside San Quentin State Prison. (22s)

What These Walls Won't Hold | Preview

Video has Closed Captions

Preview: S12 Ep3 | 30s | A filmmaker chronicles his journey beyond walls after being incarcerated at San Quentin. (30s)

What These Walls Won't Hold | The Root of Incarceration

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S12 Ep3 | 32s | Rahsaan Thomas talks about incarceration and why people get involved in crime. (32s)

What These Walls Won't Hold | Trailer

Video has Closed Captions

Preview: S12 Ep3 | 1m 8s | A filmmaker chronicles his journey beyond walls after being incarcerated at San Quentin. (1m 8s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipSupport for PBS provided by:

Funding for America ReFramed provided by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, Wyncote Foundation and Reva and David Logan Foundation.